Research Round-Up: Black Lives Matter

Black Lives Matter protests across the US, the UK, and other parts of the world have brought issues of racial inequality again to the forefront of policy discussion. In response to the anti-racism movement, we are publishing an edition of the Research Round-Up which highlights existing evidence of the systemic racism in the UK that contributes to race-based gaps in various economic indicators. Amongst indicators, the greatest disparity between ethnic minority households and White households exists is in measures of household wealth, reflecting centuries of white privilege that have negatively and disproportionately impacted ethnic minorities’ ability to achieve economic security.

The current pandemic has further exposed the harsh realities of these longstanding and persistent inequalities, as there have been disproportionately higher numbers of Covid-related deaths in ethnic minority groups and these groups are amongst the most financially impacted by the lockdown. No group, regardless of age, gender, or ethnicity, should be systematically or institutionally excluded from achieving economic well-being. We at Fair4All Finance are committed to doing more to increase the financial inclusion of ethnic minorities in the UK and are engaging in internal discussions to identify and execute our role in dismantling structural racism in the financial sector and beyond.

We will continue to update this Round-Up with additional research. It is important to note that this Round-Up focuses on racial economic inequalities; however, to better understand issues around policing in the UK we recommend the Runnymede Trust’s Justice, Resistance, and Solidarity Report.

Published reports

Are Some Ethnic Groups More Vulnerable to COVID-19 Than Others?

Lucinda Platt and Ross Warwick, The Institute for Fiscal Studies, May 2020

This report brings together evidence of the unequal health and economic impacts of the coronavirus pandemic on the UK’s ethnic minority groups, specifically Indian, Pakistani, Bangladeshi, Black-African, and Black-Caribbean. The research illustrates that racial disparities in the coronavirus crisis are most likely to manifest in two ways: (1) through exposure to infection and health risks, including mortality; and (2) through exposure to loss of income.

Health risks

In England, White British ethnic groups (who account for almost 80 per cent of the total population) have recorded similar numbers of covid-related hospital deaths (per capita) to Pakistani, Black-African, and Bangladeshi groups. However, per capita deaths for people with Black-Caribbean heritage is three times higher than the White British majority, and the ‘Other’ (based on ONS groupings) Black group has also recorded a disproportionate number of hospital deaths. There are two key factors—age and geography—that seem to push in opposite directions in terms of the vulnerability of most ethnic groups to infection from the virus. On the one hand, ethnic minority groups are on average younger than the White British majority, meaning they should have fewer deaths per capita from the virus. However, minority ethnic groups are disproportionately likely to reside in urban centres, where most coronavirus cases have been confirmed, increasing the likelihood of exposure. Regardless, the report notes that fatalities from Covid-19 among most ethnic minority groups are much higher than would be expected given their age, sex, and location.

The report also highlights occupational risk as a key consideration when analysing the differences in Covid-related deaths across ethnic groups. While many workers have been furloughed, have lost their jobs, or are working from home, ‘key workers’ continue to face risk of exposure to the virus. Research finds that those working in health and social care may be at the greatest risk, and a large proportion of these workers are from ethnic minority groups. For example, Black-Africans make up 2.2 per cent of the working-age population but comprise 7 per cent of nurses. Nurses account for the largest share of deaths among NHS staff (majority of them were from ethnic minorities).

Loss of income

Researchers also discuss the economic fallout following the government-imposed lockdown. The effects of this fallout are experienced differently, as different sectors and household-types are more or less exposed to the effects of the restrictions. Researchers find that Bangladeshi and Pakistani men are four times more likely to work in shut-down sectors than White British men, and the Black-African and Black-Caribbean men are both 50 per cent more likely than white British men to be employed in these sectors. In addition, Pakistani, Bangladeshi, Black-African and Black-Caribbean people are less likely to be living in households with two or more earners, reducing the likelihood that ethnic minority households have an income buffer throughout this period.

The report also finds that among working-age Bangladeshi, Black-Caribbean and Black-African individuals, only approximately 30 per cent live in households with enough savings to cover one month of household income, and around 10 per cent can cover three months of income. This is compared to 60 per cent of working-age individuals in the UK with enough savings to cover three months of income.

In addition to loss of income, disruptions to educational attainment are likely to have long-term consequences. There are much higher proportions of ethnic minority children compared to White children that are currently in education. This leaves these groups more vulnerable to effects of the crisis on education/schooling.

The Colour of Money: How Racial Inequalities Obstruct a Fair and Resilient Economy

Runnymede Trust, April 2020

The report illustrates that race-based economic and social inequalities can be explained by two primary factors: (1) demographic features that make ethnic minority groups more likely to experience inequalities that other similarly positioned groups also experience; and (2) discrimination.

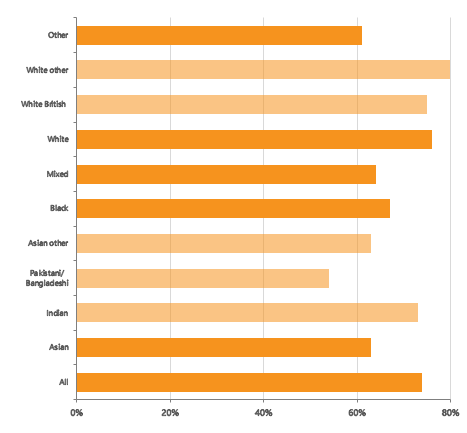

Research finds that there are significant race-based inequalities in the UK labour market, where some groups have lower employment rates and wages, and higher unemployment rates. These inequalities originate in the history of economic relations between Britain and other countriesand are persistent across all ethnic minority groups; however, it is important to note that there are disparities in outcomes for different groups. Overall, the research illustrates that there is a difference of just over 10 per cent between the proportion of employed ethnic minority people and the overall population (Figure 1). In addition, ethnic minority women have very high unemployment rates, roughly 19 per cent for Bangladeshi, Gypsy-Traveller, and Arab women.

Regarding income, there is a sustained ethnic penalty in earnings for Bangladeshi, Black, and Pakistani groups, and they are more likely to be living in poverty. Researchers find that 18 per cent of Bangladeshi workers, 11 per cent of Pakistani and Chinese workers, and 5 per cent of Black-African and Indian workers are paid well-below the National Minimum Wage, compared to only 3 per cent of White workers. This is, in part, because they are a younger population and are more likely to work in the ‘grey’ economy; however, racial discrimination in the workplace is also a cause.

Figure 1: Employment rates, by ethnicity (2016)

The jobs where ethnic minorities are typically employed are not only low-paid, they also have less room for progression, training, and wage increase. In addition, researchers highlight that, until the 1990s, all ethnic minority groups did worse in school than White British pupils. Despite improvements in racial disparities in education, the long-term effects of under-attainment will affect labour market outcomes for many decades.

Research also find that Black-African and Bangladeshi households have 10 times less wealth than White households, and that, compared to White households, levels of savings and assets are significantly lower across all ethnic minority groups.

In addition, the report highlights different policy decisions in the past that have unequally impacted ethnic minority households; namely, (1) the Benefit Cap, and (2) the Government’s decision to remove child poverty targets and change the definition of child poverty. Ethnic minority households are disproportionately impacted by the benefit cap, partly due to higher housing costs in England’s large cities (especially London) where these groups are more likely to reside.Additionally, the new definition of child poverty includes divorce, alcohol abuse, and educational attainment. This means that child poverty rates for many minority ethnic groups is downgraded, as children are doing better in school and parents are less likely to drink or divorce. These are both examples of policy decisions where racial inequalities were not appropriately assessed.

The report calls for 10 key recommendations to combat systemic racism in the UK:

- Rethinking the economy must include migration and citizenship policies.

- Reforms or changes to the economy generally should be monitored to ensure they also tackle racial inequalities, and additional policies should be adopted if they do not.

- Universal policies or systemic changes need to ensure they reach ethnic minorities. This could be achieved through working with Black and minority ethnic community groups to adapt a particular approach, or through providing language translation and/or English as a second or foreign language support.

- Those working to change economic outcomes should use statistical tools or modelling to assess how their reforms would affect ethnic minority groups.

- Discrimination should be tackled directly through better enforcement of existing laws (e.g. in the labour market, policies could include targets, and the ‘Rooney rule’ (i.e. must have one minority ethnic person shortlisted for each role advertised).

- Wider structural changes to the economy must be used to also tackle racial inequality.

- Any activities or institutions looking to change the economic system must ensure there is room for activities that tackle racist and sexist attitudes.

- Given the economic starting point of racial inequality, anyone seeking to redesign the economic system needs to consider whether the political economy should be ‘sufficientarian’ (everyone has enough) or ‘egalitarian’.

- Measures to assess various issues should assess the representation of ethnic minority voices/perspectives.

- Systems thinking on the economy must develop short-, medium-, and long-term strategies to account for existing racial and structural inequalities.

Race Disparity Audit: Summary Findings from the Ethnicity Facts and Figures Website

Cabinet Office, October 2017 (Revised March 2018)

The Race Disparity Audit was announced in August 2016 to cast light on how ethnic minorities are treated across public services. This report provides an overview of the main findings from the Audit. The data is presented across eight categories: communities, poverty and living standards, education, employment, housing, crime and policing, criminal justice, and health.

- Communities: In 2011, 19.5 per cent of the population in England and Wales identified as an ethnicity other than White British, and 13 per cent (7.5 million) stated they were born outside of the UK. The report also highlights feelings of ‘personal well-being’ for the different ethnic minority groups. In 2016, adults from Indian backgrounds reported the highest average ratings for life satisfaction, happiness, and feeling life is worthwhile; conversely, adults from Black backgrounds reported the lowest ratings across these three measures.

- Poverty and living standards: Asian and Black households are more likely to be poor and the most likely to be in persistent poverty. The report notes that 1 in 4 children in Asian households and 1 in 5 children in Black households were in persistent poverty. This is compared to 1 in 10 children in White households. In addition, research illustrates that Pakistani and Bangladeshi people were the most likely of all ethnic groups to live in the most deprived neighbourhoods (according to the Indices of Multiple Deprivation).

- Education: Chinese and Indian pupils showed the highest attainment and progress throughout their education and high rates of entry to university; whereas Gypsy and Roma, or Irish Traveller pupils, had the lowest attainment and progress, and were the least likely to stay in education after age 16. Overall, when considering Black ethnic groups, pupils made more progress than the national average. However, Black-Caribbean pupils fell behind. Regional differences in educational attainment also exist. In 2015/16, the best attainment and progress in state primary and secondary schools was in London, where more than half of the children were from ethnic minorities. Moreover, children eligible for free school meals in London had higher attainment than children eligible for free school meals elsewhere.

- Employment: Employment rates have increased for all ethnic groups, but substantial differences remain in their participation in the labour market; around 1 in 10 adults from a Black, Pakistani, Bangladeshi, or Mixed background were unemployed compared with 1 in 25 White people. Although women from Pakistani and Bangladeshi backgrounds were the least likely to be employed, the proportion who are in work has increased substantially since 2004.

- Housing: In England, African, Caribbean, ‘Other’ Black, Bangladeshi, Irish and Arab groups, or the Mixed households are the most likely to rent social housing. As a group, ethnic minority households are also much more likely to rent privately than the White British majority and to spend a higher proportion of their income on rent, regardless of whether they rent from a social or private landlord.

- Crime and policing: In 2015/16, the risk of being victim of a crime was highest for adults from Mixed, Black, and Asian backgrounds, and the fear of falling victim to a crime in the next year was also highest for these groups. People’s assessments of their confidence in police also varied by ethnicity, as confidence levels were lower among Black adults and those from Mixed backgrounds (by six percentage points compared to White adults). Confidence was lowest among young adults from Black backgrounds, as only 3 out of 5 Black young people had confidence in the police. In addition, ethnic minority people were over one and a half times more likely to be arrested than White people and were three times as likely to be stopped and searched.

- Criminal justice: Of all defendants, including juveniles, who are remanded for indictable offences, the proportion who are remanded in custody (rather than allowed bail) was highest for Black males (and Black defendants overall). In addition, the average custodial sentence length (ACSL) for indictable offences has increased for all ethnic groups since 2009, with White offenders consistently receiving the shortest ACSL. In 2014, rates of reoffending ranged from 29 per cent among Black offenders to 18 per cent of those in the ‘Other’ ethnic group (reoffending rates do not take into account important factors such as the nature of the offence or the previous number of offences).

- Health: There are differences between ethnic groups across a range of health-related outcomes. More than half of adults across all ethnic groups (other than Chinese) are overweight (particularly so for White and Black ethnic groups). In the general adult population, Black women are the most likely to have experienced a common mental disorder, such as anxiety or depression in the last week, and Black men were the most likely to have experienced a psychotic disorder in the past year. However, White adults were the mostly likely to receive treatment for a mental or emotional problem, and of those receiving therapy, White adults experienced the best outcomes.

The report also notes that the public sector workforce is a major employer, but ethnic minority employees are concentrated in the lower grades or ranks, and among younger employees.

News and blogs

The Racial Debt Gap in the UK Disproportionately Affects Black and Asian Households

Structural inequalities and systemic barriers in the UK mean that ethnic minorities are disproportionately affected by debt. The article highlights that persistent poverty is a source of this debt, however there are other factors involved. The impact of migration and cultural attitudes toward money may also be a contributor. For example, in many cultures’ money is perceived as ‘taboo’, meaning that children are not getting financial literacy training at home to prepare them for the future. Although cultural factors may impact unequal levels of debt across the country, the ethnic pay gap is likely to be the largest contributing factor, as people simply don’t earn enough money to live. White British workers earn an average of 3.8% more, and the gap rises to 20% for some ethnic groups. This means that ethnic minority groups affected by this pay gap face a higher risk of getting into debt. Between 2015-18, Black household were the most likely out of all ethnic groups to have a weekly income of less than £400.

Another reason why the article states minority communities might find themselves disproportionately affected by debt are that first-generation children must ensure their parents are financially stable, even after leaving the home. This adds additional pressure to achieve academically despite structural disadvantages that impede them financially.

Banks Biased Against Black Fraud Victims

This article summarises evidence from Cambridge University that finds that Black victims of fraud are more than twice as likely to be denied a refund by their banks as white customers. One explanation for why banks might be less likely to believe ethnic minority customers is because of stereotypes. The persistent narrative that various countries, like Nigeria and Afghanistan, are “corrupt” likely extends to the banking sectors perception of people that come from those countries. Institutional racism in the banking sector leads to lack of access of finance, such as mortgages and credit, for ethnic minority groups. This lack of access to finance is a key cause of the ethnic wealth gap, which further prevents people from owning homes and setting up businesses. Therefore, alongside police, schools, and universities, the banking sector should also be interrogated for perpetuating stereotypes and colluding in institutional racism.

Published academic papers

Payday Loans and Household Spending: How Access to Payday Lending Shapes the Racial Consumption Gap

Raphael Charron-Chénier, Social Science Research, 76, 40-54, August 2018

The paper seeks to understand if Black households in the United States use payday loans to alleviate a gap between their ability to spend and their core needs. It is well-established in literature that Black households have lower spending levels than White households in the US, for both essential and non-essential spending. This implies that Black households experience deprivations in access to basic goods and services relative to socioeconomically similar White households. Researchers find that Black households with access to payday loans are able to increase their consumption levels relative to both White households—narrowing the racial spending gap. This suggests the main alternative to payday lending is forgoing some consumption; therefore, rather than eliminating current predatory options, the researchers advocate for policy initiatives that increase access to high-quality small loan products for groups who are not well-served by traditional financial institutions.