Blog: Illegal money lending and the changing credit market

Following Stop Loan Sharks Week our Markets and Consumer Insights Manager, Niall Alexander looks at the changing credit market and the increasing lack of options for people in financially vulnerable circumstances:

‘If you know how to spend less than you get, you have the philosopher’s stone’ said Benjamin Franklin 250 years ago. Sadly for millions of households another famous quote from him is now more relevant: ‘If you would know the value of money, go try to borrow some.’

There’s an acute issue emerging for millions of people in the teeth of the cost of living crisis who cannot survive on the income they have. When many of these households need cash from lenders, they increasingly cannot get any.

During the pandemic there was much talk about how Britons had paid down their debt and accumulated savings. Like many things there was truth in some, but not all, of these assertions.

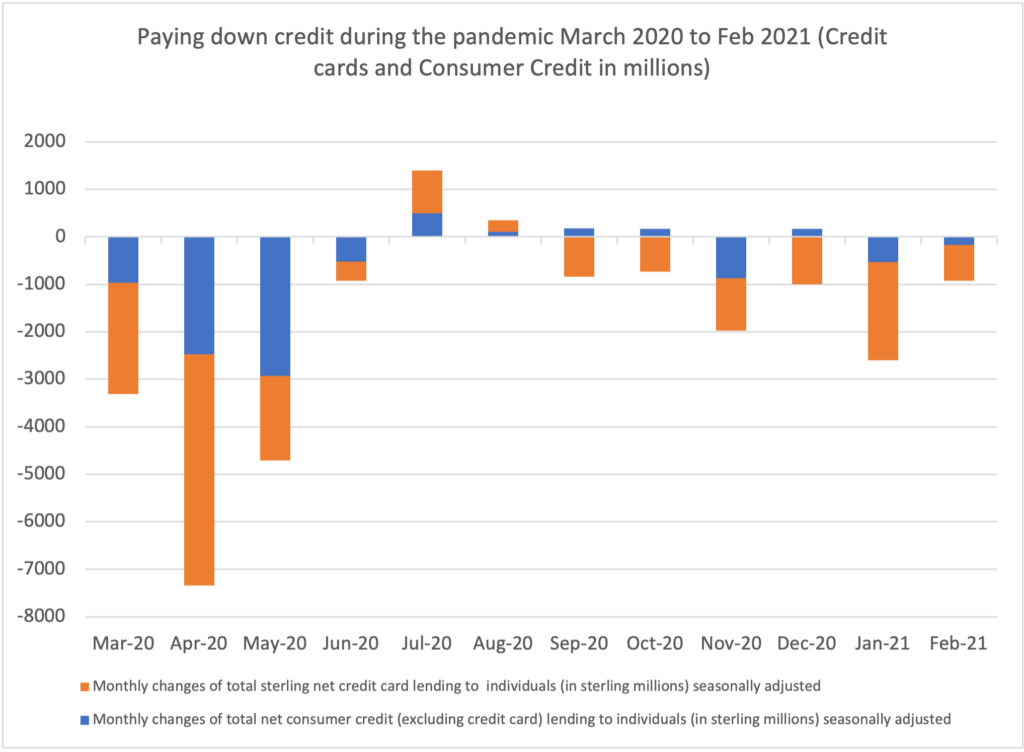

In the first year of lockdown, from March 2020 to February 2021 (inclusive) Britons paid down nearly £15b of credit card debt and a further £7b plus of outstanding consumer credit loans, illustrated below:

This was the pandemic savings bonus. Household savings were rising, reaching a peak of 23.9% in Q2 2020 (the ten year average between 2010 and 2020 was 7.3%). Those were the headlines but not the whole story.

The unintended benefit of working from home or furlough to (mostly) above average income households was savings. Savings on the commute, the Pret A Manger lunches, the after work drink, the holiday abroad and, for some, the opportunity to make inroads into their debt or credit card bills.

However, this wasn’t true for everyone. Lockdown was essentially much better for higher income households than lower income ones. It was those low and lower income households who were predominantly the ones still leaving the house at 7am to work. Hospital staff, key workers, delivery drivers. Increasingly wary of public transport, there was a surge in used car purchases. Moneybarn reported that 33% of their car sales in 2020 were to people classified as key workers. For those on roughly £25,000 household income and less, their need for credit didn’t decrease, it increased.

In parallel, the traditional lenders to lowest income households were in retreat.

In Q1 2018 High Cost Short Term Credit (HCSTC) issued 1.261m loans. By Q1 2022 this figure was just 182,000 – a drop of 86% (Source: FCA PSD006). Home credit, traditionally used by those on the lowest incomes, issued fewer than 100,000 loans in Q1 2022.

With the restructuring of Provident Financial and their withdrawal from the market alongside others, this is a sector that has run out of road from its heyday a decade earlier. No new entrants have been approved in the past three years in either the HCSTC or Home Credit markets (Source: FCA).

Many commentators welcome this but surely the withdrawal of legal credit, albeit high cost, is only welcome if the alternatives are fairer, better and, crucially, available.

With forms of high cost credit in retreat, £1b fewer has been issued by HCSTC and home credit in the two years to 2021, equivalent to around 3.25m individual loans. Community finance, whilst growing, is not of the scale yet to step in to fill the displacement gap. Equifax reported in July 2022 that ‘demand for credit, evidenced by search volumes, has now returned to pre pandemic levels.’ So where will people turn if they need a line of credit?

Choices are becoming increasingly limited. Lenders tighten their criteria during recessions and we’re seeing this happen. Applications haven’t dropped, but it appears that approvals as a percentage of those applications have. The cost of living is keeping demand high. Data on Demand reported in a Fair4All Finance webinar that in April 2022, 10% of all applications for HCSTC were for loans to pay household bills. Three months later this figure was 54%.

Friends and family borrowing has escalated. In 2017 the FCA reported 3.6m people used friends and family. This figure rose to 5.9m in Feb 2020 with a prediction it would reach 10m.

Borrowing from friends and family may be benign at times but it is also finite. It will be increasingly difficult for one low-income borrower to borrow from another, especially when that other person is also struggling to make ends meet. The Centre for Social Justice (CSJ) reported earlier this year that they thought 1m people in England were borrowing illegally. We’ve been working with all four illegal moneylending teams across the UK, the CSJ and the Consumer Credit Trade Association (CCTA) on our own research into illegal moneylending.

Since the summer we’ve commissioned two extensive pieces of research examining both physical, relationship based lending and the emergence of digital lending as credit markets tighten and credit declines increase.

We have researchers working in four towns and cities (Preston, South London, Glasgow and Port Talbot) speaking to both illegal moneylenders and borrowers. Our researchers have gathered over 75 people so far, including eight lenders, to speak on tape about their experiences and motivations.

The early assessments are of links to other criminal activity including money mules, identity theft, heavy use of Buy Now Pay Later and some evidence of continued doorstep lending from unlicenced lenders – so called parallel lending.

We’re hearing about people with few choices seeking credit. Stress, violence, intimidation, and for borrowers a feeling of necessity. Our researchers aim to speak to over 150 lenders and borrowers by the time their field work has concluded.

We have a separate research team looking at the impact of tighter regulation and credit declines – an imminent 2,000 person survey will examine whether the retreat of high cost credit is having an impact on people’s credit destinations.

There are no easy answers to complex public policy challenges. We are engaged in promoting and supporting scalable community finance, it’s a steep hill but one that we need to climb.

Mainstream finance surely must come to the party too. They supported households during the pandemic with payment holidays and £500 overdraft facilities. They could, indeed should, see their role as society wide – their shareholders increasingly demand it of them and regulators through consumer duty will have expectations of them.

This is a wicked problem, in the sense that it is persistently resistant to resolution, rather than evil. Credit, whether we like it or not, has a role to play in modern Britain and we should do all we can to ensure it is a policy and regulatory priority, as well as a strategic priority for those financial services businesses who are able to help. The consequences if we don’t pay attention could be grim.